Many philosophic, moral, and religious principles say that people should be treated as equals (e.g., UNDHR) or that some people,  such as non-combatants, should receive special protection (see IHL).

such as non-combatants, should receive special protection (see IHL).

One way to measure prejudice is to test how people believe different kinds of people should be treated.

People higher on social dominance orientation prefer policies, like the U.S. invading and controlling other countries, that treat powerful groups better than others (e.g., Pratto, Stallworth, & Conway-Lanz, 1998).

Prejudice can change what other scholars view as fundamental psychological processes, such as loss-aversion in decision-making.

Theory-Driven Research on Real World Conflict

A series of experiments tested what decisions people would make about the lives of people in different nations at war: their own,  their ally, and enemy nations.

their ally, and enemy nations.

Usually when people are asked to choose between certain and uncertain gains, they choose certain gains. But when asked to choose between certain and uncertain losses, they choose uncertain losses (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). This is an insight of Prospect Theory.

We studied how U.S. and U.K. participants valued the lives of non-combatants and combatants regarding the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan (Pratto, Glasford, & Hegarty, 2006; Pratto & Glasford, 2008).

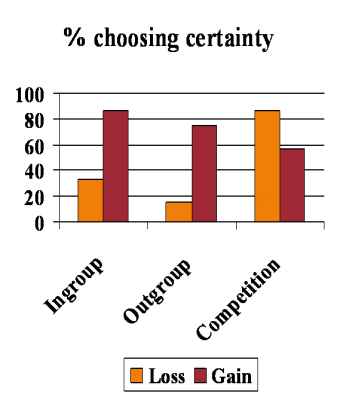

In one experiment, between-subjects, participants decided whether they would prefer decisions that either would save (“gain”) or lose lives. They had to chose whether outcomes would be certain or uncertain.

- In the “ingroup” condition, choices were about citizens of participants’ nations.

- In the “outgroup”condition, choices were about citizens of Iraq or Afghanistan.

- As shown, most people did choose certain gains and uncertain losses for each country considered alone.

- When considering the lives of just one nation, even an enemy nation, most participants

would save lives for sure and try not to lose lives for sure. (see left & middle of graph to right).

Whose Lives Matter?

But what if the choice was between combatants from participants’ own nation and civilians from an enemy nation? In the “competition”condition, choices about participants’ own nation and Iraq were in competition: Participants were asked to chose between ce rtain losses for Iraq and uncertain losses for their own nation, or between certain gains for Iraq and uncertain gains for their own nation. Most people made the prejudiced or ethnocentric choice: certain losses of Iraqi civilians and little preference to save Iraqi lives (see right of graph above).

rtain losses for Iraq and uncertain losses for their own nation, or between certain gains for Iraq and uncertain gains for their own nation. Most people made the prejudiced or ethnocentric choice: certain losses of Iraqi civilians and little preference to save Iraqi lives (see right of graph above).

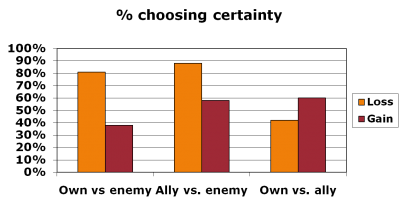

In decisions that pitted lives of people from participants’ own nation, ally nation, and enemy nations, people treated the ally nation much as their own nation, and valued its lives more than those of enemy civilians. Interestingly, people who rejected these choices were the most opposed to the war! (see graph on left).

Ethnocentric Indifference

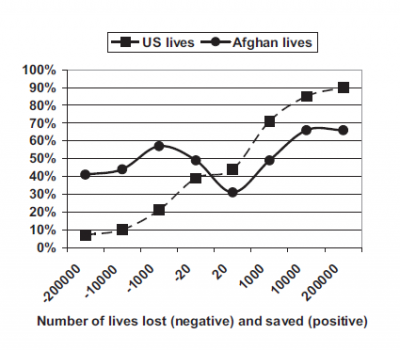

In other experiments, participants were asked to choose between a number of lives for one side and a material outcome, such as an increase or decrease in the unemployment rate or price of fuel, for the other. People were strongly influenced by the number of lives at stake for their own country– sacrificing material gains to save more lives, and taking on material losses to prevent more loss of life. However, the number of lives at stake did not matter much to them when they were “enemy” lives. This was true even if the decisions pitted combatants from one’s own country against civilians from the other. (Pratto & Glasford, 2008). We call this “ethnocentric indifference to magnitude.” The graph on the right shows the number of participants would would chose to lose or save the number of lives shown on the X-axis rather than take on an material loss or gain (Pratto & Glasford, 2008, Experiment 1).

Ethnocentric Prejudice in Decision-Making

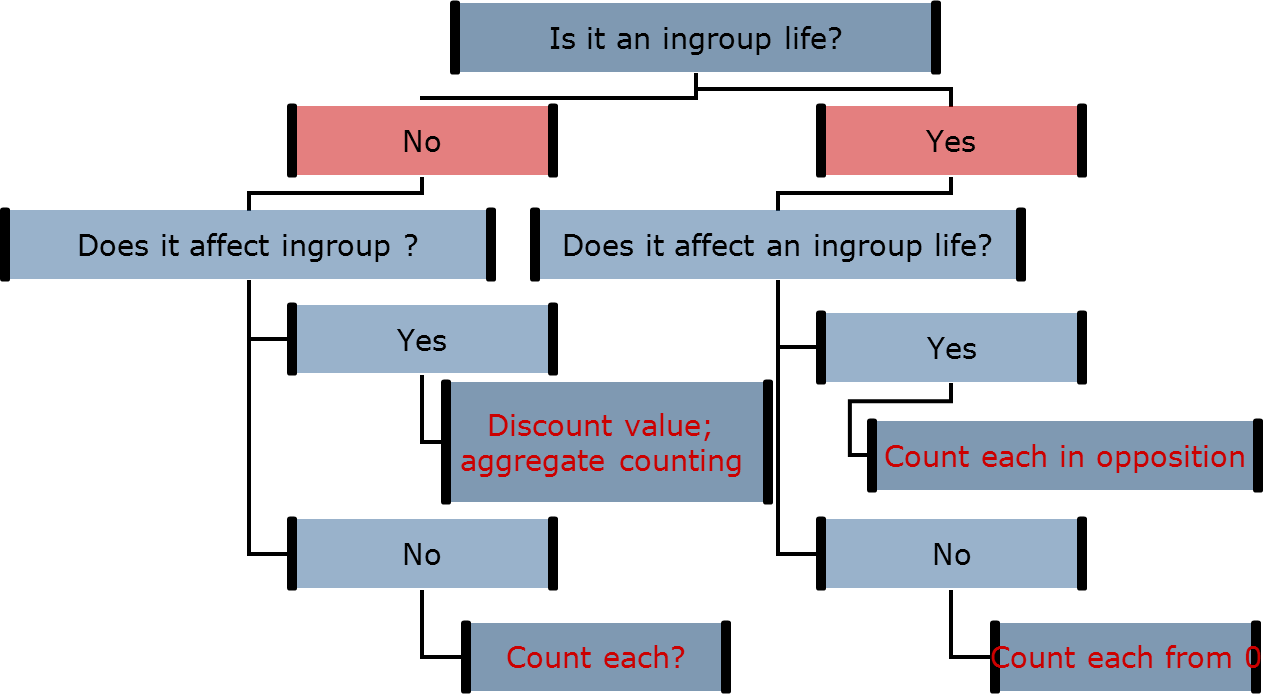

In summary, our US and UK participants try to avoid loss of life, even for enemy nations. But if decision choices pit their own country or ally against enemies, they will chose losses of life and fail to save lives, even in violation of protecting non-combatants. From this research, it appears that it is as if people decide on how valuable people’s lives are following these decision rules (see Pratto & Glasford, 2008):